Chess Literacy

By STEVE CROSS

Staff writer

- How to get strong

- How to play blindfolded

- How to write your own chess program

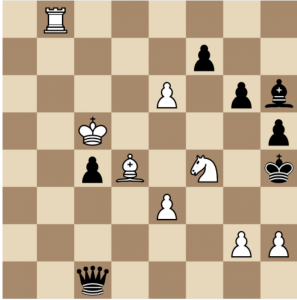

White to play and win (solution at end).

Unless you have experience solving studies, we suggest you spend a couple minutes trying, then just enjoy the solution. This study is an example of a position you’ll soon be able to solve quickly in your head — if you practice the visualization exercise below, and the unified approach to tactics in the next column.

The first 49 pages of Lev Alburt’s “Chess for the Gifted and Busy” is all you need to be chess literate, and win most offhand games in a coffee shop.

Then, fill in the details with Emanuel Lasker’s “Manual of Chess.” Lasker was world champion and a mathematician of the late 19th and early 20th century.

If you’d rather go directly to learning the basic algorithms and writing a chess program, read “How Computers play Chess” by Levy and Newborn.

To get strong quickly and learn to play without a board — blindfold chess — Alburt’s book gives exercises to learn the color of each square, visualizing the board and the practice of finding paths between two squares for a piece. He calls this a Chess “meditation,” giving the example of finding a path from g1 to c4, for instance g1 – f3 – d2 – c4. He also recommends making up you own visualization exercises — finding all paths between the two squares. This simple exercise can improve your concentration and your grades in other subjects, such as math, and reduce study time.

Solution to study:

1.e7, qa3+; 2.Rb4, qa7+; 3.Kxc4! , qxe7; 4.Nxg6+, fg; 5.Bf6+, qxf6; 6.Kd5+, Kg5; 7.h4+, Kf5; 8.g4+, hg; 9.Rf4+, bxf4; 10.e4# — Alexander Kazantsev